But what are you, inquiry-based learning?

Those three little words ‘inquiry-based learning’ really seem to get thrown around a lot in teaching. Almost like the magic recipe to teaching adolescents, keeping them engaged, and making learning meaningful. So we dig deeper into it: what is it, how is it done, and is it really manageable in our classrooms?

What is inquiry-based learning? Good question. Breaking it down to the words, by definition it should be learning that is based on asking for information. The same way I inquire with my mechanic about how much the brake pads will cost to replace. Or I inquire amongst my friends to know if they have a go-to seamstress in town. I’m asking for information. According to Lee et al. (2004), they define inquiry-based learning as “array of classroom practices that promote student learning through guided and, increasingly, independent investigation of complex questions and problems, often for which there is no single answer” 1. I did some reading through Queen’s University’s Centre for Teaching and Learning, where they break down inquiry-based learning.

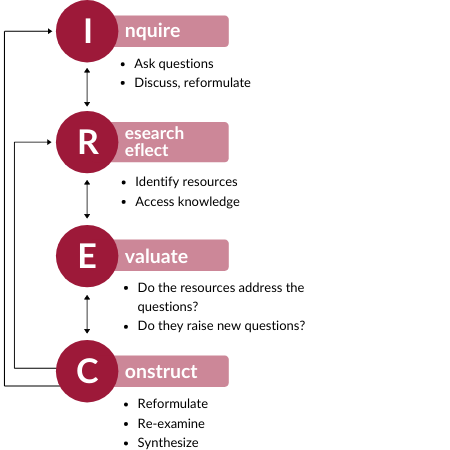

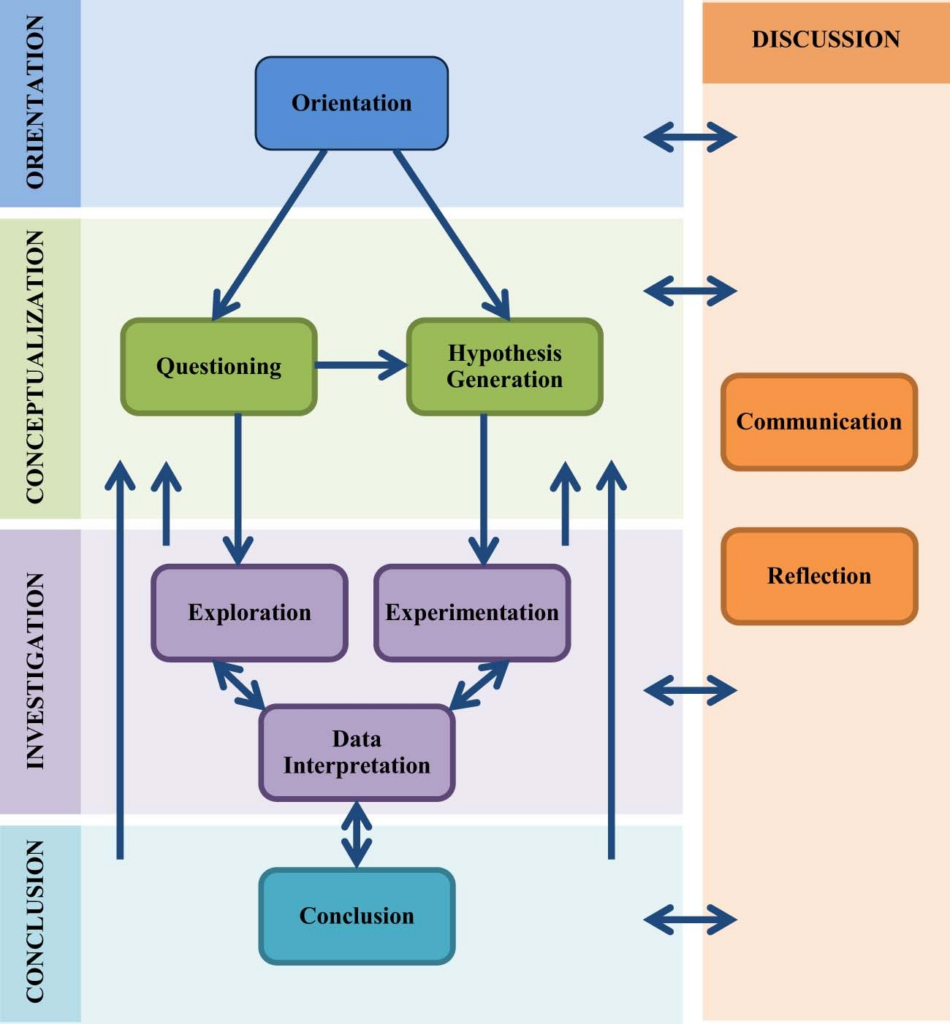

Inquiry-based learning is not only for learning to ask the right questions to answer your complex problem. It also involves learning how to set goals, manage time, communicate thinking and learnings, think critically, gather information, and assess 3. On the right, you can see a flowchart of inquire-based learning from Ai et al. (2008). What I appreciate from this flow chart is how the arrows loop. I think this is vital because learning is ongoing. As a scientist, I knew that learning was never done. We do research, hypothesize, test, conclude, and adjust for our next trial. We look to make errors so that we can show holes in our predictions, and to prevent them next time. I think involving this process in learning is vital.

How is inquiry-based learning done? I’m not sure there is one real answer for this, however there are many models in the works that allow us to adapt them to our own teaching tool belt. After our visit to The Pacific School of Innovation and Inquiry, I recognized how this learning method can be done in an immersive way. Through student-led learning, holistic education, and breaking down constructed ways of assessing achievement, PSI has began the development of this model. Upon reflection, I do believe this model of school works fantastically for certain types of students, while may be totally out of reach for others. However, it made me think about how an inquiry-based learning approach can be done in one classroom. For myself, I know this is something I want to bring into my future science classrooms. I remember in grade 11 for science fair I drafted and built a prototype of a wheelchair made out of bamboo. For this project, I had to “solve” a social issue in another country. I chose Laos, and found a large issue to be the lack of wheelchairs accessible to the population. So I dove into natural resources and what could be readily available. I ended up competing on a provincial level, and won some awards from universities.

Science is an inquiry-based field. It’s what we’re built on. How do we reintroduce native plants to soil highly impacted by heavy metal pollution? Why is antibiotic resistance on the rise? How do loons know how to get back to their lakes after winter? The figure on the left shows the phases of scientific inquiry-based learning. They are all student led, and are all linked to each other. Once you get to conclusion, the arrows bring you back to ‘conceptualization’ because that is it; you loop back to your questions you asked in the first place 5.

So to see inquiry-based learning dripping into other subject areas, is quite refreshing. I’m not saying we do it perfectly in science classrooms, but we kind of have the foundation to be able to excel in it. How can we do more? Bring inquiry-based learning into projects such as: science fairs, term projects, naturalist journals, lab design and journals, to name a few.

Is it manageable in classrooms? Short answer – yes. While so many factors play a role in the accessibility of learning on the inquiry-based learning scale, I believe we may be overcomplicating it. For example, this middle school science classroom in Boulder, Colorado shows how inquiry may not be coming up with a complex project, but providing a question and then allowing students to work on finding a solution.

“The answers are always just a little bit out of reach for the kids until they really reach a point where they have a sense of discovery” – Ian Schwartz